Best American Hip-Hop Albums of 1997

- October 15, 2025

- 0

The article reviews the best American hip-hop albums of 1997, highlighting influential works by artists such as The Notorious BIG, Wu-Tang Clan, Busta Rhymes, Master P, Jay-Z.

The article reviews the best American hip-hop albums of 1997, highlighting influential works by artists such as The Notorious BIG, Wu-Tang Clan, Busta Rhymes, Master P, Jay-Z.

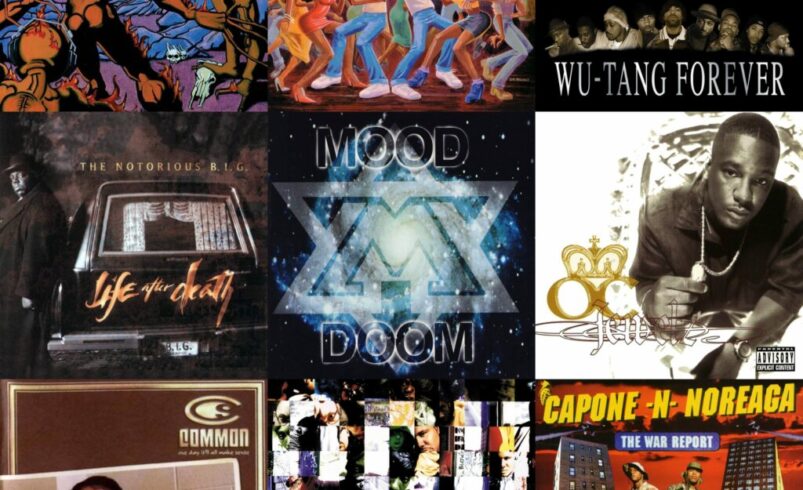

The second album of the “King of New York”—a young, hot-tempered, very large, and serious guy with the disarming charm of a street genius and killer. The success of the debut album “Ready To Die” three years earlier made Biggie the main hope of New York’s true school for chart domination. His double opus was prudently handed over to insider producers under the collective name The Hitmen, led by his boss and best friend Puff Daddy. However, in addition to this, star producers RZA, Easy Mo Bee, Havoc, and, of course, DJ Premier were invited to create the sound. Therefore, the album is loaded with classic R&B, but heavily seasoned with the gloomy handwriting of New York gangsta—both in the beats of about a third of the tracks and in most of the lyrics. By the release, Biggie was in the position of an undisputed leader, whose success irritated too many people, especially since six months before its release, his opponent 2Pac was killed. Two weeks before the release, Notorious BIG himself was sent to heaven by several shots through the car door.

Why you should listen to this. Biggie was a powerful lyricist with his own special melody, a predatory intensity, and an air of superiority. Starting with captivating storytelling, he could then switch to a party anthem listing the signs of his wealth and success, continue with an aggressive representation aimed directly at haters (and even in the lyrics, expressing outrage that the beatmaker of this very track, DJ Premier, has the audacity to communicate with his, Biggie’s, enemies!), then delve into crude and sweet corners of R&B, write a wild story about beef (not Twitter squabbles, but real beef when you are afraid to start the car and leave your mother alone in the city), teach young people how to sell crack, and then share a story of his own rise, from which even the listener might grow wings. Life After Death provides a comprehensive idea of the sound that was at the height of fashion in 1997, while giving preference to the East Coast in its most hit-oriented embodiment. The swing and fun are importantly wisely balanced by Biggie‘s trademark nihilism and brutality.

What happened next. If Chris Wallace had been a little more cautious—not going to the West Coast and preserving his life—then, with such a hit-making sense and winning decisions, he could have been destined for a brilliant prolonged career, which would have adjusted the real biographies of his fellow countrymen like Jay-Z or DMX. But the departure of such a valuable player beheaded New York rap for a couple of years, paved the way for other young people, including Biggie‘s partner Sean “Puffy” Combs, and left only a handful of verses from the artist himself, which were spread by his followers across several boring and unnecessary posthumous releases. Life After Death belongs to that unique circle of rap albums that sold over 10 million copies, and quotes from Biggie’s lyrics consistently appear in new rap compositions each year.

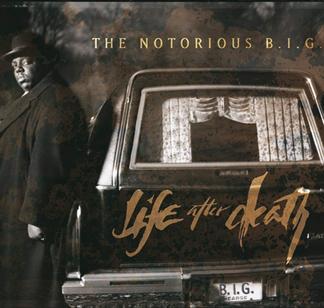

The second, this time double album in the fashion of the late 90s, by the cult New York group, shining with its style in the spirit of oriental martial arts and the philosophy of black supremacy. A real magnum opus. Unlike the 1993 debut, each of the nine MCs in the collective had their star moment here, and beatmaker and inspiration RZA led an orchestra of revolutionary electronic sounds and solemn melodies for that time.

Why you should listen to this. The album became multi-platinum against all odds. It is gloomy and cold, there are almost no easy choruses, harsh and masculine themes are raised, and the verses are overloaded with verbose MCs with sharply differing styles. The first single, Triumph, is simply eight verses over a grim loop. Apparently, the drive with which RZA directed the album played a role, thinking only about making it unlike anything that had come out then. If Biggie’s album is all the best hip-hop could do in 1997, then WTC is what it didn’t even try to understand. But quality and zeal did their job.

What happened next. From 1993 to 1997, RZA was a dictator in the group. But after WTC, he abruptly released the reins, and the guys quickly deteriorated. The discography of the microphone ninjas was cluttered with R&B choruses and second-rate shell made on the knee. Over the next three to five years, the group gradually eroded its previously impeccable image, enjoying only individual solo successes. Solo material has to be carefully filtered by fans of the group. RZA writes music for films, GZA travels with rap lectures about the universe’s structure, Method Man lost his touch in making good albums, ODB is dead, Raekwon is two blocks from Narnia, Inspectah Deck went underground, U-God never came out from there. All hope is on Ghostface, and now Masta Killa has released a good solo album.

The bright second album of the crazy New Yorker, screaming and slapping with open hand in the face, without any limits or brakes. Busta gathered his small gang Flipmode Squad and kept his beatmakers, who made an accelerated and frantic version of East Coast rap for him, very fashionable and unusual for the masses, hitting somewhere in the middle between pop Bad Boy, gloomy Wu-Tang, and breakthrough Timbaland.

Why you should listen to this. The late 90s was the peak period for Busta Rhymes as a relentless rhymer and supplier of hundred percent hits. Every verse of his is like a napalm spit, every single an impudent claim to superiority, and everything in his image, from the lyrics to the choreography and clothing, is maximally authentic and talented. Moreover, the album is very candid and angry. There is plenty of darkness, porn, fighting, and schizophrenia.

What happened next. By the mid-2000s, Busta Rhymes cut his locks, grew fat, and lost the heat in his delivery, turning from a fashionable freak into a well-fed boar. He’s still capable of spitting like a machine gun, but he can’t or doesn’t want to make hit singles. However, the best albums by Busta Rhymes sound as bright and wild 20 years later as they did back then.

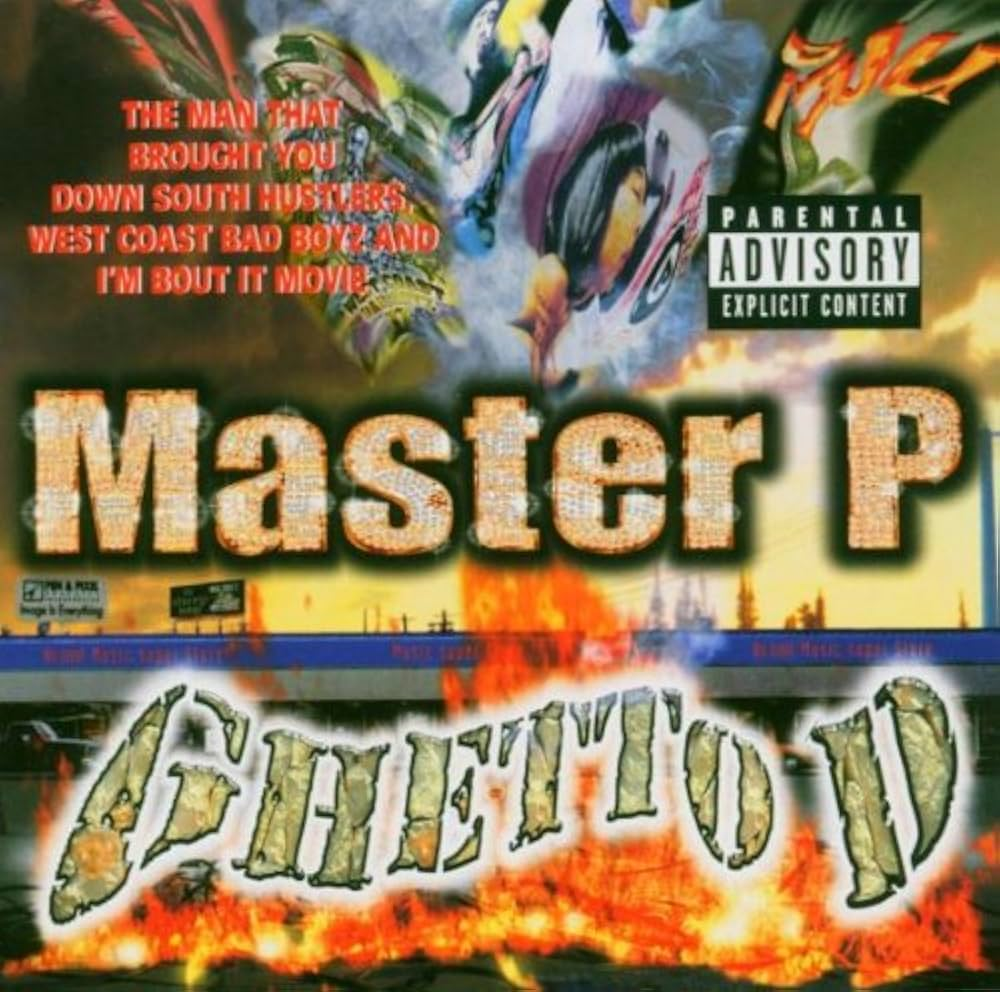

Yes, this piece of fried southern style is called exactly that—“Ghetto-D,” although it is known everywhere under its censored title, where only the D from the Dope remains.

Successful underground businessman Percy Miller gathered his brothers and neighbors from the slums of New Orleans to create a new empire of rap bandits, with a completely new sound and dense southern flavor. An unprecedented torn sound in the boom-bap rap universe was the work of the Beats By The Pound team, and twenty hoarse throats telling wild stories from the stuffy alleys of black suburbs, with the smart and stubborn Master P at the helm.

Why you should listen to this. This is southern folklore as it is, with a breakthrough sound for that year and a terrible accent. The sense of immersion is very strong—these guys seem to have jumped off the streets just yesterday. They don’t really know how to rap, they tear lines, confuse rhymes, tracks are mixed crookedly, choruses are bluntly sung over old soul hits, so as not to bother. It’s dirty and true. And it was from this that the division of the American rap scene into three “shores” instead of two began, and it was from here that the victorious series of southern sound started, which lasts to this day.

What happened next. The era of No Limit Soldiers‘ hegemony was very short. In the following 1998, P flooded the market with albums of his second and third-rate buddies, as everything he released sold like hotcakes. Even the number one star Snoop Dogg joined the label, and the first of his three albums with them is their best disc in 1998 and his worst album (which should say something about the label’s release quality). But by 2000, sales quickly fell, and the best ran away from the ship, for example, Snoop Dogg and Mystikal. P several times reassembled the lineup, but soon became a caricature. His middle brother went to jail, the younger quickly got tired of rap, and the rest of the gang scattered. Master P remained a successful businessman, but rap took a backseat. However, we must remember who opened the South’s way to the top.

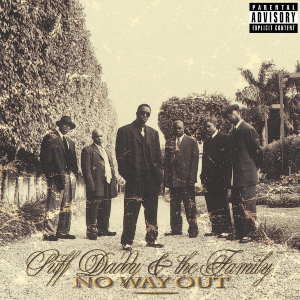

A rather carefree (considering the recent death of Bad Boy label’s best artist Biggie), fully consisting of soul samples, producer album where the boss’s personality does not get lost among the mass of guests. Young Puffy had to rely on Biggie’s guest verses, but he did the beatmaking work masterfully, and within a year turned into the ruler of the charts.

Why you should listen to this. At the time of release, the album might have seemed shamelessly commercial. The first single was a tribute to the late Biggie, recorded as a cover of the Police group hit. How much simpler and dumber? Exactly the same way all the other tracks of the album were cobbled together. But over time, the borrowings lost their negative connotation, while excellent work in stitching these patches together remained. Well, the opening track Victory is just a bomb, and even after so many years, it remains unrivaled.

What happened next. Puffy’s album earned a Grammy, at the moment of awarding which Ol’ Dirty Bastard rushed onto the stage with a scream that although the album is good, the Wu-Tang Clan is still the best, because they are for the kids (!?!). Puff developed his label well while such sound was relevant, after which he extended his tentacles into other business assets. If at the beginning of the 2000s, his name caused a smile as a synonym for a show-off and bad taste, it gradually weighed more than his entire former label. Staying one of the most significant beatmakers in the genre’s history, Puff Daddy by income can lead among colleagues in the music sphere. Oh, and there was Jennifer Lopez in his story, that’s true.

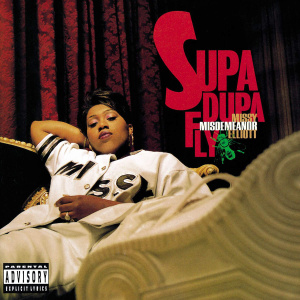

What kind of album is this. A futuristic female album where everything was new and unique—boldly unlike the classical sound from the young Timbaland, with confident flow and unintrusive vocals, caustic sense of humor, unconventional way of thinking and natural talent of the artist from Virginia. She moved to New York in the early 90s with Timbaland, with whom she formed a producer duo. These two managed to create many hits for young stars of R&B, including the early deceased Aaliyah, so by the time Missy started her solo career, she was already a grown-up and experienced girl.

Why you should listen to this. Missy Elliott is bright, bold, sexy, technical, and her sound is aimed at the future with a big reserve. Missy and Timbo opened new horizons and challenges for female rap and mainstream hip-hop. Electronic sound here became dominant over the warm boom-bap, and bright form prevailed over street authenticity. Well, as a woman, Missy behaved defiantly but didn’t fall to the level of microphone sluts like Lil Kim.

What happened next. For about ten years, Missy led female rap, bombarding the public with expensive futuristic videos and powerful material, made by her in collaboration with fellow Virginian Timbaland and other bold musicians in the genre. After which, she mostly rested, getting distracted only by infrequent production. The result of her push was six platinum-plated albums (among which the fourth, Under Construction, is generally the best-selling female rap album) and four Grammy awards. In 2015, Missy performed at the Super Bowl with a mix of her best tracks, which increased the sale of her old records several times over and even returned them to the Billboard charts. Each of her new appearances for the audience is now like a gift, as she has been building her seventh album slowly for about ten years.

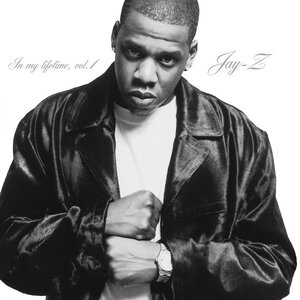

The album cannot be considered the best among the many releases of Jigga, but it keeps the bar raised by the debut Reasonable Doubt with a reserve. In addition to classic New York beats, Jay offered several reliable singles here, intentionally pop in the style of Puff Daddy and therefore unmistakable.

Why you should listen to this. Jay-Z is an iconic figure when it comes to confidence and maturity. Jigga’s character in his 25-30 years is wise and pumped in street philosophy as if he is 10-20 years older. Sometimes it seems that Jigga already knew back then how well everything would be for him. And at the same time, he almost did not betray the native boom-bap. The album fulfilled the most important function—gradually transitioning the artist from young New York classics to mainstream master.

What happened next. In the absence of the late Biggie, Jay easily tried on the crown of New York ruler, and then the whole world. The second and third parts of “Lifetime” made him the master both in the charts and among true audiences. He always knew exactly how to make a hit, and always remained insightful and daring, managing to triumph both as a businessman and an artist. He sold over 100 million of his records, collected 21 Grammys, became the second wealthiest artist in the USA after Puffy. He married one of the most desirable women on the planet, managed to cheat on her, and write wonderful songs about it.

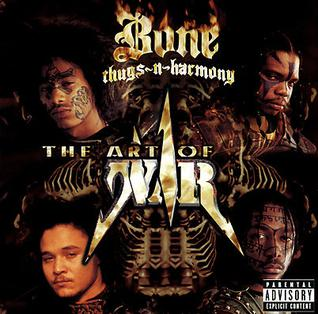

Another double disc by another supergroup, a Cleveland quartet (or quintet? one was always incarcerated) with hurried rhymes about gangster life and loyalty to the brotherhood. The massive release was fully produced by the talented DJ U-Neek, and therefore maintained in a uniform transparent, melodic design, through which gangsta-bangers rarely broke out where it was necessary. The melodic structure of the compositions in some ways resonates with the current trend of singing lines in rap verses.

Why you should listen to this. Krayzie, Layzie, Wish, and Bizzy developed their own style as if completely unaware of what was happening in the industry at that time, and therefore created a modest, but masterpiece. The rhythm is slowed compared to the general fashion, and the MCs attach their rhymes to the melody (albeit not always accurately) and constantly go into double-time. The themes of the tracks were also quite interesting, it was a special subspecies of gangsta-rap with an inclination towards military seriousness and soldier camaraderie. But when listening 20 years later, the thought doesn’t leave that BTNH’s music would generally have turned the game upside down if autotune and other tools of today’s rappers and vocalists had been in use back then. After all, it seems to have been created just for such.

What happened next. The group lost its authenticity and originality even faster than Wu-Tang, and the partial departure from DJ U-Neek‘s services completed the crisis. The collective was still capable of individual hits in the 2000s and still records in different combinations, but it sounds templated and tired. All of Bone Thug‘s pride remained in the 90s.